Rebase vs merge

During a CodeRefinery workshop you might have heard an instructor say that you can merge or alternatively rebase, like merge and rebase are two equivalent operations. Clearly, they are not, but should we treat the operations equally?

Let us take a closer look at rebase and merge, how they differ and in which situations they are an advantage to use.

Rebase

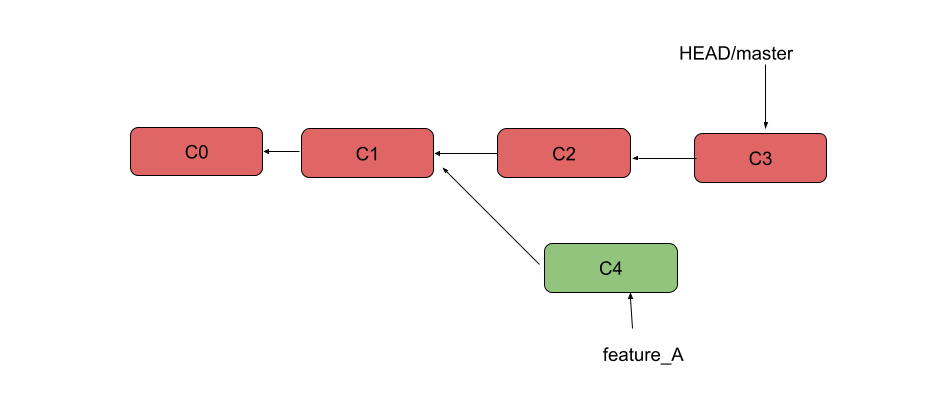

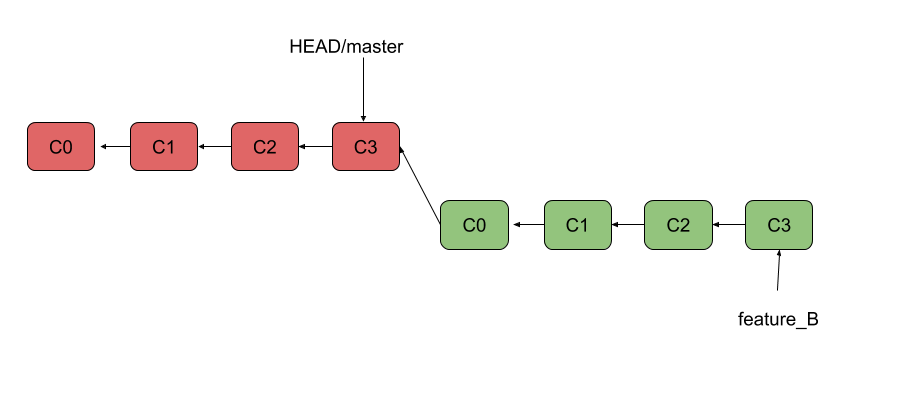

Rebase gives you the opportunity to move the base of a branch to a new

base. Here we have two branches, master and feature_A.

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

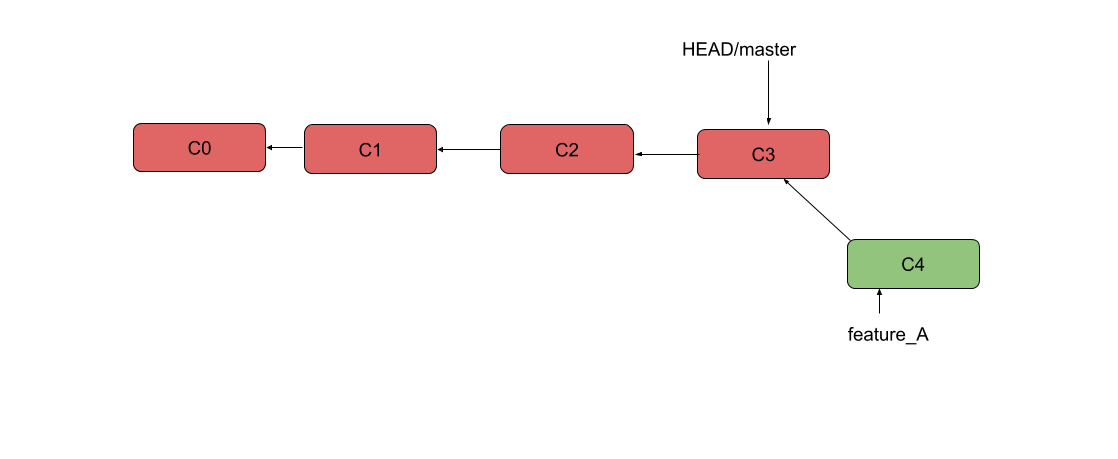

We can rebase the feature_A branch to the last commit in master:

git checkout feature_A

git rebase master

The result will look like this.

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

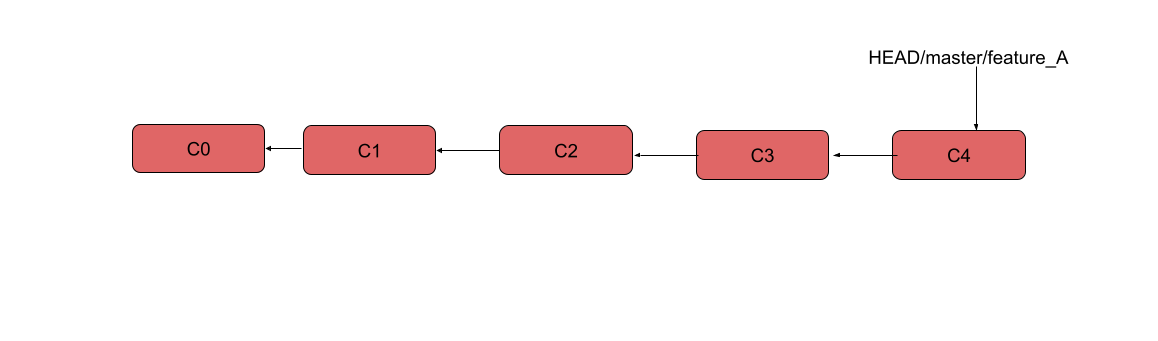

Checking out master again, we can merge feature_A with master. The merge will by default be a fast-forward. We end up with a linear history, which many find attractive as it is easy to follow. The disadvantage is that we rewrite the history as the commit hashes changes.

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

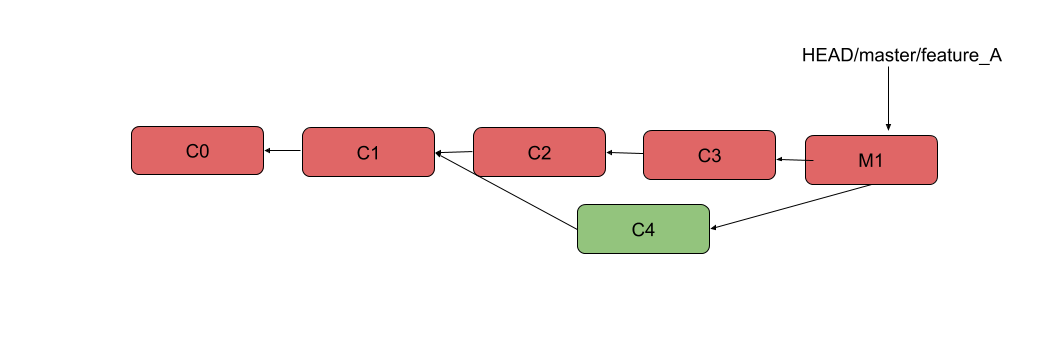

Merge

If we don’t use rebase, but just merge feature_A with master, we get an merge commit, a new commit pointing to the previous last commit in master and the previous last commit in feature_A.

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

If we only do merges, we show the true story of the repository, how the code came to be. As the repository grows with new branches, maybe more contributors, following the history can become very challenging. The git graph can look like the tracks of a large railway station, where it can be hard to find the ancestors of a feature.

Mixing rebase and merge

Instead of sticking to either rebase or merge, we could use both operations, but establish principles for when we will use merge and under which conditions we use rebase:

- When we merge a semantic unit to

master, we use merge. - When patch features, or do general corrections, we use rebase.

How will this look?

Merge revisited

Let us say we have created a new function or class, something that belongs together - a semantic unit we call feature_B. The base of feature_B is the last commit in master.

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:70%"}

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:70%"}

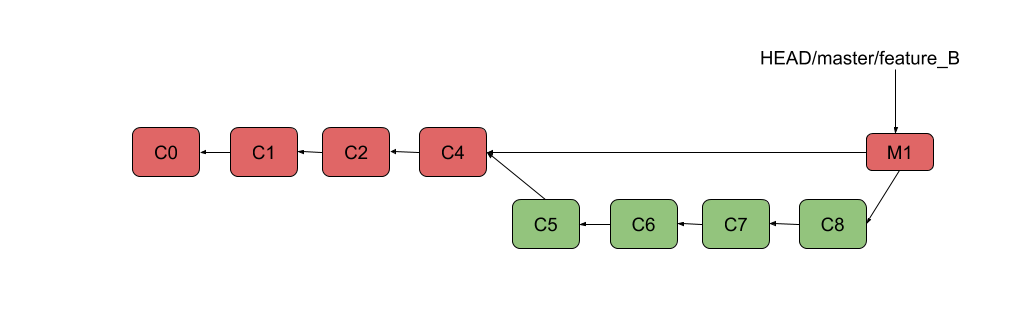

If we do a merge, git will by default do a fast-forward merge. Following our newly stated policy, we want this merge to be a merge commit. Consequently, we add the option --no-ff to the merge command:

git checkout master

git merge feature_B --no-ff

Alternatively, we can configure git to default do merge commits, by setting the configuration to not do fast-forward by default. Here as a global setting, spanning all our projects:

git config --global branch.master.mergeoptions --no-ff

The result will be like this, where the feature is clearly visible in a feature path, presumably with well written commit messages explaining what has been added in this path of work.

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

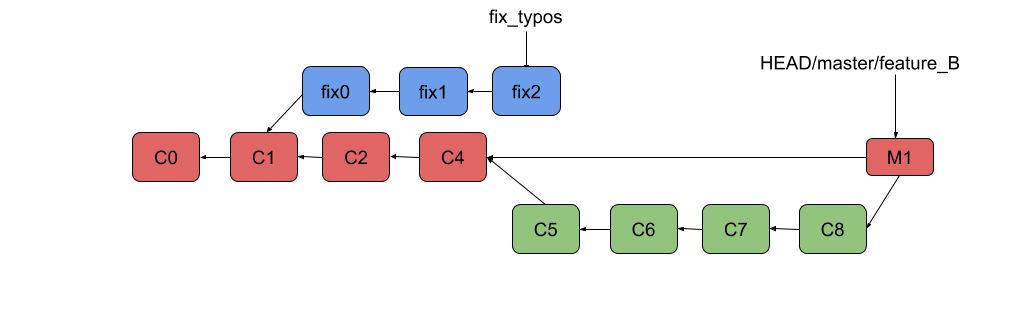

Rebase revisited

Now we take the case where we checkout a branch from C1 to do some corrections. While we were doing the corrections, at least before we were able to complete the corrections, master moved to M1 as in the picture above. A merge commit will add unnecessary complexity to the story of our project. We are not adding a new semantic unit, just fixing things that got wrong in the first phase. That we started to fix things from C1 is not necessarily a important information to keep for the project.

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

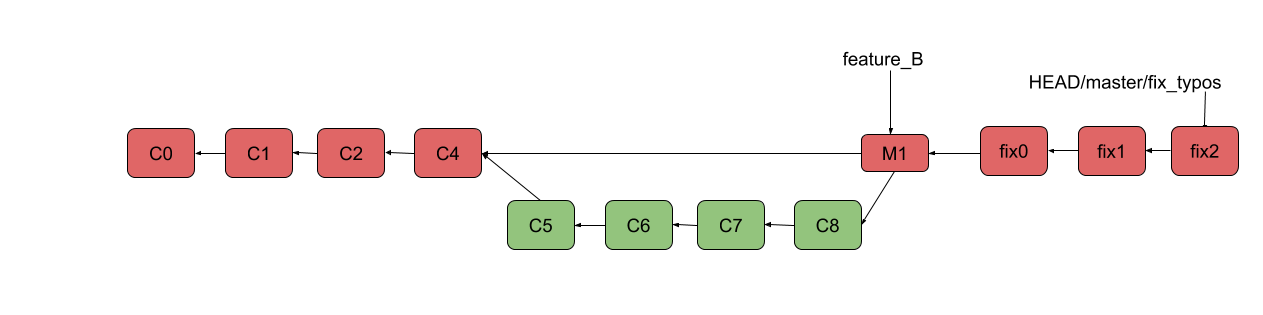

Following our second principle, we rebase the fix_typos branch to M1. Then we do a merge, but this time as fast-forward. If we have configured merge for not doing fast forward when possible, as the configuration statement above, we need to add the --ff-only argument:

git checkout fix_types

git rebase master

git checkout master

git merge fix_typos --ff-only

The git graph will now look like this:

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

{:class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%"}

Rebase vs merge revisited

Rebase and merge serve two different purposes. We can use this to our advantage to create a clear story, a more readable git log (It is important to create a story, remember?). By using the above principles as guidance, we will become more conscious of where these operations will serve us or add more clutter. For instance, we might conclude that rebasing semantic branches, but insisting on a merge commit, is perfectly fine, because it is where the feature (the semantic entity) enters the master branch which is important, not where the development first started. Features will clearly stand out as a visible pattern in a git repository following such a practice.